Even though the Best Novelette nominees include one bad story and one weak one, they are still a stronger group than the Best Short Story slate. Taking the bad news first . . .

The most that can be said for

“TelePresence” by Michael A. Burstein is that it is not quite so atrocious as his short story nominee

“Seventy-Five Years”. In

“TelePresence”, which concerns a virtual reality classroom that turns deadly, Burstein is at least trying to address an issue worth considering: equality in education. (Never mind that he addressed the same issue in the same way in his 1995 story

“TeleAbsence”.) But whatever point he has to make is undercut by his awkward prose and stiff characters. To give just one of a great many examples, this is Burstein's description of a teenage murder victim, from his protagonist's point of view:

Catherine Harriman's body lay slumped in her simulator. Her head hung to one side, with her tongue lolling out of her mouth. Her eyes were frozen open, glassily staring at nothing.

How horrible, he thought.

What is the last line doing there? Are we readers so dense we need it explained to us that the murder of a young woman is horrible? Perhaps I could forgive such sloppy writing if Burstein had something interesting to say on the subject of school violence, but he offers no new insight at all. The murderer's ultimate explanation of his motive is so unconvincing that I honestly thought for a moment Burstein meant it as parody.

Burstein’s unconvincing details make matters worse. For instance, he sets his story in California but seems to know nothing about the place. Anyone who has lived in California could have told him that a group of public school commissioners from Sacramento would not be all-white, would not be thrilled at the prospect of traveling to Los Angeles, and would not panic at the sensation of an earthquake in virtual reality. Combine this lack of basic research with Burstein’s amateurish prose, and this story’s Hugo nomination is another embarrassment to the field.

While not quite so embarrassing, it is difficult to figure how Howard Waldrop’s

“The King of Where-I-Go” got its nomination. There is no SF element for over half of the story, just a series of tangents about how iron lungs and linotypes work. When it finally arrives, the SF element proves to be a tired, and surprisingly straightforward for Waldrop, time travel scenario. I think the tale is designed to produce a sense of nostalgia, with lots of old pop culture references à la Harlan Ellison’s

“Jeffty Is Five”, but it did not work for me on that level. Waldrop is too skilled a writer for me to call this story bad, but it sure ain’t good.

Thankfully, the other three Best Novelette nominees are all worthy of award consideration. They also make for a nice cross-section of the SF/F genre, as they include a light-hearted science fiction romp, a somber dystopia, and a high fantasy.

The romp is Cory Doctorow's

“I, Robot”. Ostensibly a detective story, the plot is really just an excuse to take us on a dizzying tour of a future world in which the West and the East have followed different approaches to A.I. technology, with the West’s approach showing some unintended consequences of Asimov’s Three Laws. Doctorow says he wanted to expose the “totalitarian assumptions” underlying the Asimov universe, but he gives the East’s approach a pretty creepy outcome as well. I suspect this story may have the best chance of winning the award, simply because it is very fun to read. I have to rank it third, however, because I never came to care about the characters as I did reading the two remaining nominees.

“Two Hearts” by Peter S. Beagle is the high fantasy, in which a headstrong young woman seeking to defend her village against a marauding gryphon enlists the aid of characters from Beagle’s classic

The Last Unicorn. The story is very enjoyable and elegantly written. It also takes a bittersweet look at the ravages of time that is far more effective than anything in

“Down Memory Lane”, discussed yesterday. My only qualm about giving the award to this story is that it really is a companion piece to

The Last Unicorn, not a stand-alone story. In particular, if you haven't read the novel, this story will seem to have a

deus ex machina resolution. Then again, what excuse does anyone have for not having read

The Last Unicorn by now?

“The Calorie Man” by Paolo Bacigalupi is the dystopia, set in a future in which food shortages are so severe that wealth is measured in terms of calories. The world is dependent on an American megacorporation’s patented genengineered grain for food and energy because – rather suspiciously – plague and pestilence have wiped out all of the world’s other grains. Our protagonist, a refugee from a devastated India, travels the Mississippi River in pursuit of a faint hope of changing the status quo. Like

“I, Robot”,

“The Calorie Man” proceeds from interesting, if unlikely, speculations about where future technology could lead us. Unlike

“I, Robot”, it shows us this world through the eyes of people with whom we can identify strongly. Paolo Bacigalupi doesn’t write very much, but he does write very well. I would dearly love to see him write more SF, and what better way to encourage him than to give him a Hugo Award?

Aaron's Ballot:1. Paolo Bacigalupi – The Calorie Man

2. Peter S. Beagle – Two Hearts

3. Cory Doctorow – I, Robot

4. Howard Waldrop – The King of Where-I-Go

5. NO AWARD

6. Michael A. Burstein – TelePresence

Predicted Winner:Cory Doctorow – I, Robot

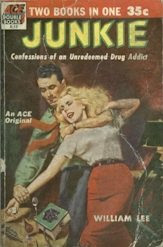

The Book of the Week is Ace Double D-15, by far the most collectible of the Ace Double line. Published in 1953, Ace D-15 combines two early novels in the "juvenile delinquent" genre: Junkie by William Lee and Narcotic Agent by Maurice Helbrant. Junkie is the important one. Junkie was a first novel, detailing the unknown author's real-world struggles to overcome his heroin addiction. The book was ignored when published, but retroactively became famous when William Lee turned out to be the pseudonym of William S. Burroughs. After writing Junkie, Burroughs managed to overcome his addiction and become a hugely influential Beat Generation author, famous for such avant-garde works as Naked Lunch and Nova Express. Among the many artists Burroughs influenced were a number of authors in science fiction's New Wave and cyberpunk movements, and British SF magazine Interzone is named for one of his books. (You knew an SF connection was coming, didn't you?)

The Book of the Week is Ace Double D-15, by far the most collectible of the Ace Double line. Published in 1953, Ace D-15 combines two early novels in the "juvenile delinquent" genre: Junkie by William Lee and Narcotic Agent by Maurice Helbrant. Junkie is the important one. Junkie was a first novel, detailing the unknown author's real-world struggles to overcome his heroin addiction. The book was ignored when published, but retroactively became famous when William Lee turned out to be the pseudonym of William S. Burroughs. After writing Junkie, Burroughs managed to overcome his addiction and become a hugely influential Beat Generation author, famous for such avant-garde works as Naked Lunch and Nova Express. Among the many artists Burroughs influenced were a number of authors in science fiction's New Wave and cyberpunk movements, and British SF magazine Interzone is named for one of his books. (You knew an SF connection was coming, didn't you?)